By: Tracey Evans, AKFC Program Manager

Across Aga Khan Foundation’s global education programs, I’d often heard about school classrooms that held upwards of eighty, one hundred, even two hundred students at one time. These crowded classrooms can be the result of a government’s new policy that ensures free schooling for every child, or caused by a significant influx of refugees arriving in some of our program areas because of a neighboring country’s conflict. The implications crowded classrooms have on the students’ ability to learn are important. They can lead to lower learning outcomes and grades, leave children feeling discouraged, and potentially motivate children to leave school in pursuit of low-skill, informal work.

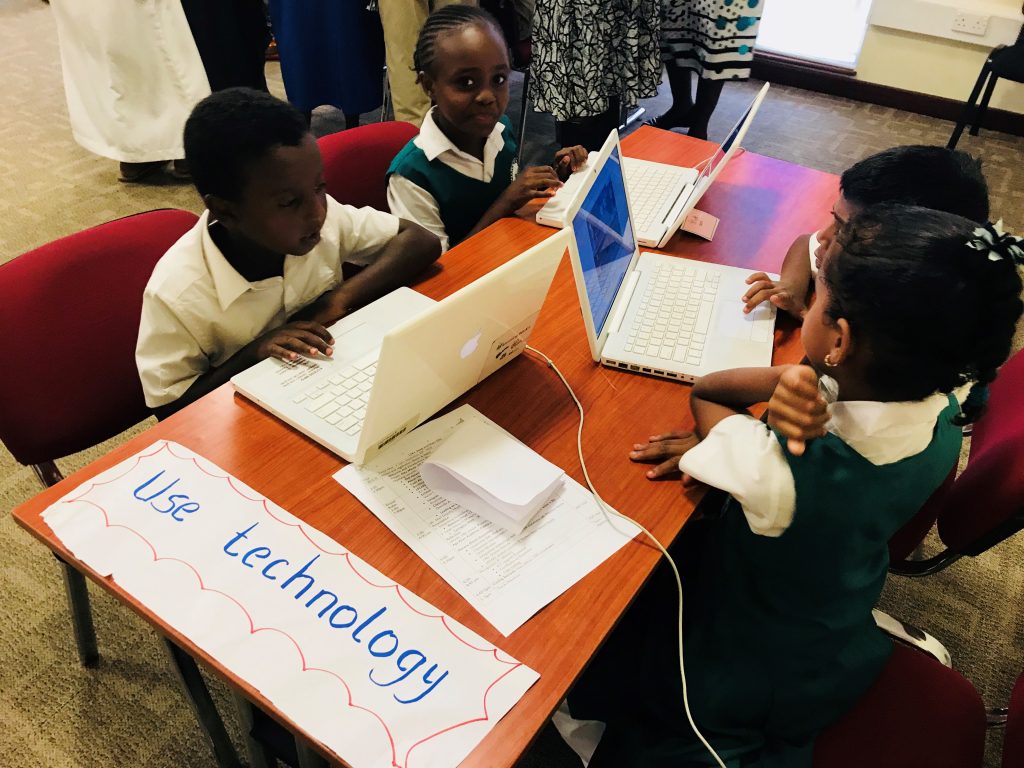

In a recent visit to Mombasa, Kenya, I was exposed to another strategy being employed by teachers to help cope with ballooning class sizes: the use of technology.

Technology, be it through an online web portal or an offline learning app, gives students the opportunity to interact intimately with the content they are learning in a way that is not only exciting and intriguing to them, but also essential for their long-term success. From Kenya to Canada, technology skills are increasingly essential to thrive in today’s global workforce. Helping children gain these skills not only enables them to become comfortable and skilled at using technology, but also has the potential to improve their learning outcomes within an environment that encourages self-regulated learning, an essential strategy for effective, lifelong learning.

Recognizing the value that educational technologies can bring to the classroom, the Aga Khan Academy in Mombasa, Kenya has spent the past six years working with the Centre for the Study of Learning and Performance at Concordia University, to implement the Learning ToolKit (LTK+) in schools across Kenya. LTK+ is a suite of five evidence-based, proven digital tools to support the development of literacy, numeracy, inquiry, and other essential student competencies.

Used in the context of Kenyan classrooms, the toolkit has proven to be successful in accelerating learning. After visiting a few of the Kenyan classrooms using these tools, it was easy to see why.

The first classroom I visited was at full capacity, with 131 students sitting on the ground without desks or chairs. Despite these clear resource gaps, thanks to the Kenyan government’s One Laptop Per Child policy, most classrooms (including this one) are equipped with a substantive number of tablets. The room was full of laughter, whispers, and name calls until the teacher called the class to order and explained how the students were to divide themselves into small groups of two or three and use the toolkit, with each group sharing one tablet. As soon as the activity began, the power of technology was evident. One hundred and thirty one students were instantly captivated, stimulated, and challenged intellectually, leaving the teacher free to walk around the classroom and support groups individually as they had questions or struggled with an activity.

Later that same day, while visiting another classroom in a different school, I was again reminded of the desire children have to learn through technology when, looking out the classroom window, I saw students tightly pressing their faces against the window to peek inside and watch their friends use the tablets. It was clear that, for every child in the school, these digital tools had made learning a joy rather than a burden. Teachers I spoke with after my classroom visits told me that in the short time they’d been using the toolkit, they’d noticed attendance rates increase on days when they promised students ahead of time that they’d be using it, and that some students had begun requesting to come in after school hours to get more time on the tablets.

The use of technology in any classroom, let alone ones that are under-resourced and overcrowded, is not without its challenges. From weak internet to frequent power outages, the unexpected obstacles that come with using technology in marginalized contexts mean that teachers always have to be prepared with a back-up plan should technology fail them. A lack of tablets can also mean that teachers have to stagger toolkit activities with other offline work. Despite these obstacles, every teacher I met who was using the toolkit say the benefits they have seen in their students’ learning far outweigh the technological hiccups that are bound to arise.

When speaking at a teacher professional development event in Mombasa, the Teacher Service Commission County Director, Boniface Okumu, expressed how he believed wholeheartedly in the need to integrate information technology into the education system.

“If we want to make our schools interesting and exciting, we need to bring information and communications technology [ICT] into the classroom. It’s high time we change the narrative of education in the Coast Region of Kenya. It can change, and that change begins with you and me, by having us make ICT a part of the narrative”.

Tracey Evans is a program manager with Aga Khan Foundation Canada. Tracey was in Kenya to visit a research project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). This project was implemented through a partnership between Aga Khan Academies and Concordia University with support from Aga Khan Foundation Canada – and builds on a past initiatives supported by Global Affairs Canada, International Development Research Center, AKFC, and SSHRC.